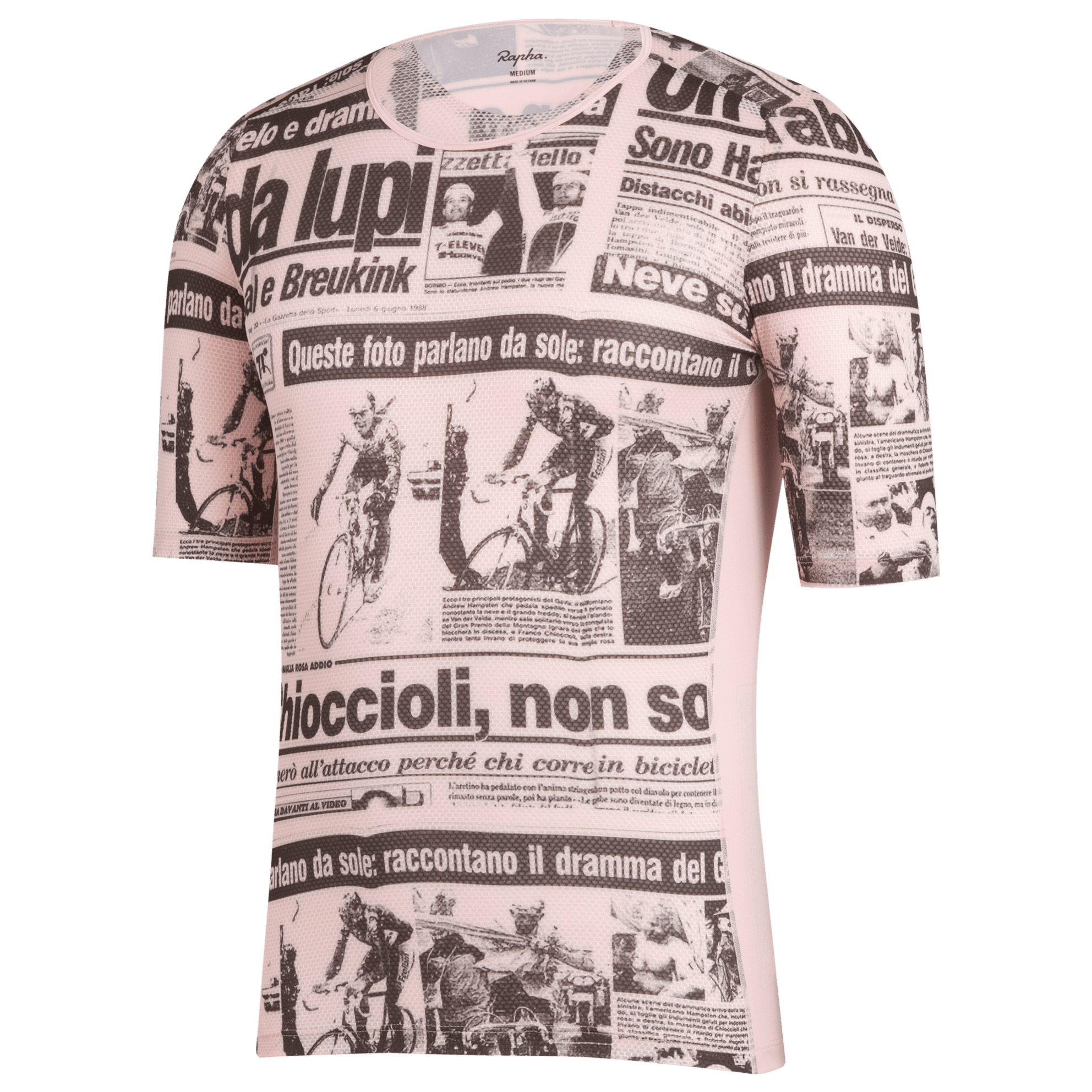

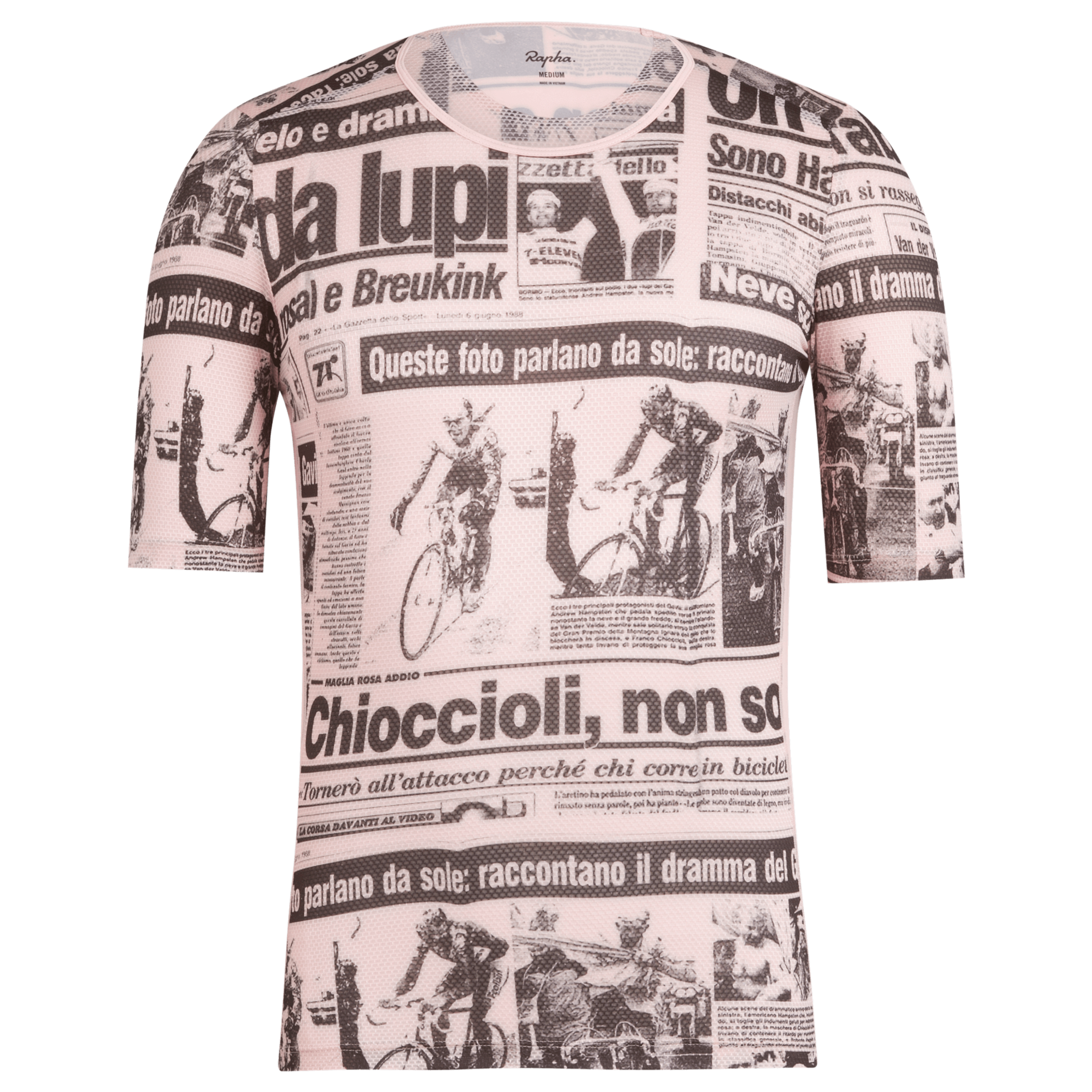

The forecast is for snow. Amid rumours of the next day’s stage being cancelled, 7-Eleven riders fan out across start town of Chiesa in search of ski jackets, neoprene gloves and balaclavas – if the forecasters are right, they’re going to need all the clothing they can find.

The next morning, the wintry weather has set in and, despite the protestations of some riders, the stage gets underway. After surviving the first climb over the Passo Tonale, the race properly begins as the peloton hits the lower slopes of day’s final climb, the Passo di Gavia. The sheets of sleet and rain in the valley below have become a blizzard on the upper slopes. The sinuous road, bordered by towering banks of snow, is disappearing fast under a thick and freezing carpet. White out.

But through it all, a flash of colour. Goggle-like, yellow-tinted sunglasses, a bright red jacket underneath the blue jersey of the leader of the combination classification. With snow settling on his head and shoulders, Andy Hampsten cuts a lonely figure as he appears out of the fog, looking more like an Arctic explorer than a bike rider.

As most of his rivals seize up with cold behind, he forges on through the storm on the stage that came to be known as the day the big men cried. With the wind howling like the wolves which, according to local legend, prowl the Gavia’s upper reaches, the American holds his advantage on the descent to Bormio, taking valuable seconds on the rest of the pack.

Andy Hampsten’s superb ride through horrendous winter conditions over the Passo di Gavia may not have brought him the stage win but was the foundation of his overall win at the 1988 Giro d’Italia. Still the sole American victor, Hampsten’s exploits in the most brutal of conditions over one of Italy’s most celebrated climbs are etched into cycling folklore.

It was an iconic day in cycling. It was a day captured with some of the most recognisable photography in the sport. It was the day the big men cried.

R