Professional cycling has not done enough to attract, inspire and emotionally connect with new fans. It is run by ex-racers for racers and die-hard fans. It has stuck to its roots, placing too much emphasis on tradition, even as other sports have evolved or expanded in new directions through reform. There are a number of key changes, discussed below, which can be made to the professional cycling calendar, organisation, competitive incentives and racing formats to enhance its relationships with existing fans and to create a compelling narrative that might resonate with new fans. Rapha believes these changes will nurture more sustainable and longer-term commitments by global investors in key cycling markets.

In this section, we will explore reform of the most visible components of the sport; the races and the riders. Whilst the structure, economics and presentation of professional cycling are of vital importance, we must start with the sport itself - the calendar, the teams and the format of road cycling as a competitive activity. There are fundamental changes, advocated by some of the most experienced stakeholders in the sport, that could be made in all of these areas to make the sport more exciting and easier to understand.

Specific consideration of the format, marketing and broadcast of women’s racing is outlined below and this research and its recommendations were compiled with the aim of parity between the two genders. The sport has the opportunity to advocate true gender equality and the roadmap within this document is equally applicable to men and women, including but not limited to an equal minimum wage for male and female riders. It has been claimed by those in the sport that there has been significant growth in the fanbase of women’s cycling, owing to the development of teams and races within the sport. In more than a dozen relevant interviews for this research, it was clear that access and engagement remains a challenge. But those difficulties are not limited to the women’s sport and it does not make sense to separate out the discussion of the sport by gender. Doing so may hinder the growth of both.

Shorten the calendar

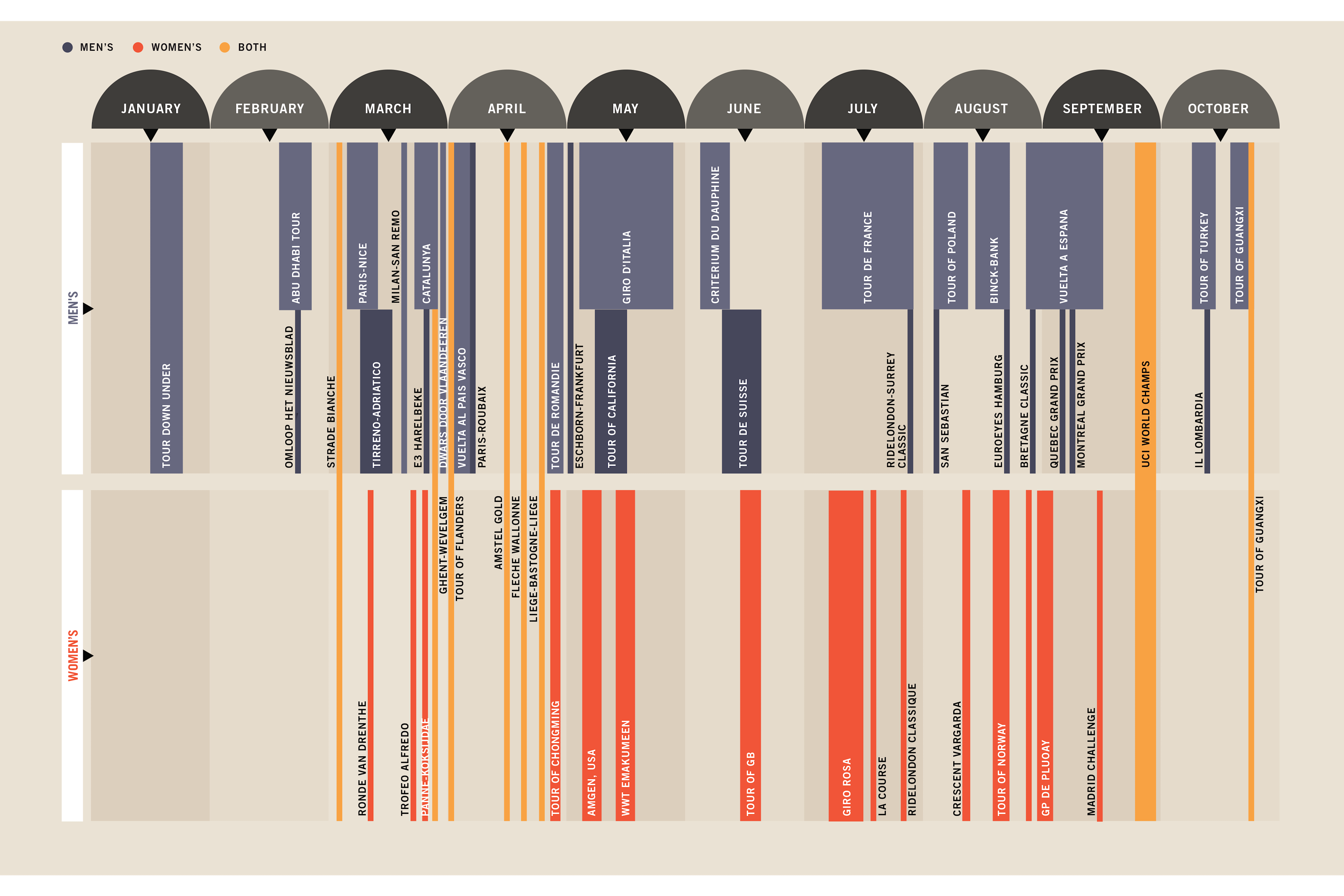

Professional cycling has one of the longest calendars of any sport, with no official on or off-season distinction. The elite road racing calendar, including the best teams in the world, runs from January through to the end of October and with a number of active competition days unusually high for major sports. The top-level World Tour format alone includes 37 different events that cover a full ten months, equating to 178 racing days a year of spectator events at the highest level of the sport. That annual offering has been more than a century in the making. The three Grand Tours - the Giro d’Italia, Tour de France and Vuelta a España - have expanded to run for a full three weeks each. One-day “classic” events, the most prestigious of which are known as the Monuments, and one-week tours have proliferated in the early months of the year (with the exception of the Tour of Lombardy, raced in October). Stage racing has been exported around the world as the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) has sought to globalise the World Tour, finding (and losing) new investors to host one-week events around the world. Organising that eclectic mix of events into a single cycling season has been fraught with challenges. Senior sources in the organisation of the professional sport have described the ad-hoc bartering that has often determined the calendar of elite bike racing. A form of consultation takes place within the existing governance system, but the structure of the sport, with no single organiser or clear priority for expansion, has led to a calendar with no clear narrative and unnecessary complication. Races often clash, putting serious strain on team and organisational resources. Even the most committed fans now face a sporadic and overlapping series of events that have little to no relation to one another, making it difficult to recognise the best riders in the sport. Few other sports have this type of congested and impenetrable schedule.

The great races in the cycling calendar date back to the early years of the 20th century, when the pursuit of cycling was, as now, an exciting, yet accessible pastime. Some of the greatest tales of cycling bravery stem from this era and were told to the world through the pages of the newspapers which often organised the events, ostensibly to improve circulation. All of the Grand Tours were established by newspapers, the first being the Tour de France, which was founded in 1903 by Henri Desgrange, editor of L’Auto (now L’Equipe). Such was the popularity of the race and the upturn in fortunes for L’Auto that the model was replicated first by La Gazzetta dello Sport in Italy with the Giro d’Italia and later by Informaciones in 1935, which founded the Vuelta a España. In the early years of the 20th century, cycle racing proved an irresistible draw for a public hungry for thrills. One hundred years on, the sport has become obese with bureaucracy, and the founding principles - to entertain - long forgotten.

It was simply a matter of time before someone attempted to introduce a seasonal structure to cycle races, and that came with the Challenge Desgrange-Colombo, which ran between 1948 and 1958. This attempted to arrange results from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and the biggest Classics to determine the best rider of the season and was run by the newspapers L’Équipe, La Gazzetta dello Sport, Het Nieuwsblad and Les Sports. Everything was going well until Classics specialist Fred De Bruyne took three consecutive wins. The organising committee, presumably concerned about the potential loss of readers, squabbled and the series was doomed.

Then in 1959 Pernod, the French distiller, expanded its involvement in cycle racing from its previous sponsorship of a season-long competition for the best French rider. The Super Prestige Pernod took the races of the Challenge Desgrange-Colombo and expanded the series to an international level.

Many of the riders in the cycling hall of fame won the series, including Jacques Anquetil with four titles in the 1960s before Eddy Merckx took it on seven consecutive occasions. Bernard Hinault won four years running from 1979 to 1982. Greg LeMond won in 1983 and Sean Kelly two years after that, before Stephen Roche in 1987. That year proved the end of the Super Prestige Pernod thanks to new French laws banning alcohol sponsorship in sport. It was already under fire, however, following the introduction in 1984 of the FICP world rankings, which later became the UCI rankings. Sean Kelly dominated these for the first five years, setting a pattern of mundanity compacted by a rolling format.

It was the UCI which eventually replaced the Super Prestige Pernod in 1989, with the UCI World Cup. This linked the Monument Classics and newer one-day races into a season-long points classification. Sean Kelly won the inaugural title in 1989, but the World Cup was treading on thin ice with its race programming, shelving historic Classics such as Gent-Wevelgem and Flèche Wallonne in preference for little-known new events such as the Wincanton Classic and the GP de la Libération team time trial. The idea was to fit World Cup races into weekend television schedules to maximise viewers while also growing the sport internationally.

The UCI called time on the World Cup and UCI rankings at the end of 2004. The calendar was a mess and team hierarchy almost non existent. Out of the ashes rose the UCI Pro Tour from 2005, with a reformed calendar.

The intentions of the Pro Tour format were to make the biggest races a draw for the best riders. By 2004 the Giro d’Italia had become a race for Italian teams. The big names, meanwhile, such as Lance Armstrong and Jan Ulrich sat out the early races, keeping their powder dry for the Tour de France in July.

In encouraging the biggest riders to take part in all of the important races, the idea was to take the popularity of cycling beyond Europe while adding a stable platform for teams and sponsors. The two divisions of the World Cup became the Pro Tour and the Pro Continental Circuits respectively. All 18 Pro Tour teams were guaranteed entry to the Tour de France, diluting the power of the ASO which previously had autonomy over team selection. With the advent of the Pro Tour, the ASO was given just four discretionary invitations.

The Pro Tour structure led to further clashes with the ASO, organisers of the Tour de France and a number of the Classics, and also with the organisers of the Giro d’Italia and Vuelta de Espana. By 2008, the three Grand Tours had pulled out of the Pro Tour altogether, as well as five of the most prominent Monuments: Paris-Roubaix, Milan-Sanremo, Liege- Bastogne-Liege and the Giro di Lombardia. The disputes came to a head in July 2008 when the 17 Pro Tour teams taking part in the 2008 Tour de France announced they wouldn’t be seeking licenses for the 2009 Pro Tour season. While they all eventually signed up, the damage was done.

UCI World Ranking was introduced in 2009 following agreements between the UCI and race organisers. Concessions were made: Grand Tour organisers retained the right to choose teams for their races and teams were able to choose not to race certain events. The Pro Tour was abolished in 2011 with all races on the World Calendar which count towards UCI World Ranking falling under the umbrella of the World Tour. Since then the World Tour has ballooned. The 2011 World Tour consisted 27 events; 14 stage races and 13 one-day races. In 2017 a further 10 races were brought into the calendar, bringing the number to 38. The theory behind the addition of more races is one rooted in making the Word Tour economically viable to sponsors and fortify team finances. More races should offer a bigger platform.

The modern cycling calendar, which does not build toward a season finale, risks losing the interest of dedicated fans, alienating new audiences, and makes it difficult to maintain and promote an annual sporting ‘narrative’. Professional cycling has never truly had an end-of-season grand finale event with which to wrap up the calendar. Traditionally, the last major race of the year was the Giro di Lombardia. However, over the last 25 years, a desire to shift the sport’s focus to a World Tour points model led to the World Championships being moved from August (following the Tour de France), and into a spot just prior to Lombardy. The World Tour points championship has in turn struggled for credibility and the UCI World Championships often don’t feature all the star riders, for whom the Tour de France is a primary racing objective, and who essentially end their seasons prior to October. As a result, the crowning of a “World’s best rider” and “World Championship Team” is all but impossible. Without a developing narrative and a more coherent calendar, professional cycling cannot build to a crescendo and the sort of “victory parade” or end-of-season finale that characterises most other sports.

The calender at a glance

The men’s 2018 World Tour calendar consists of 37 races, of which 20 are one-day races, 14 are multi-day races around a week in length, and three are three-week Grand Tours - all told, men’s World Tour teams could compete at the elite level for 178 race days in 2018, starting in mid-January and ending in late October. By comparison, the 2008 Pro Tour calendar, the predecessor to the World Tour, required teams to attend just 15 races (owing to disputes between race organisers and the UCI over inclusion of certain events in the Pro Tour), with teams exercising more choice in filling the gaps in their race calendars.

Aside from their designation as WorldTour races, there is a de facto hierarchy within the calendar, with the oldest races possessing a special status - these races are referred to as Classics, with the five oldest, hardest, and most prestigious one-day races referred to as Monuments: Milan-Sanremo, Tour of Flanders, Paris-Roubaix, Liège–Bastogne–Liège, and Tour of Lombardia. The last major change to the professional calendar came in 1995, when the Vuelta a España moved from August to September to alleviate the congestion of staging the three Grand Tours between May and August, and the World Championships moved from late August to late September.

The women’s World Tour calendar runs from early March through to late October, and in 2017, had 20 events, 14 one-day races and six stage races, with 46 days of racing in total.

A comparable hierarchy exists in the women’s calendar, with older races considered Classics and Monuments, although there are no races longer than 10 days in length. In 2018, no new races were added to the men’s calendar, while the women’s expanded with new races in Spain, Belgium and China. Both men’s and women’s World Tour teams will also race at non-World Tour races, either in preparation for bigger races, to appear in ‘hometown’ races, or due to sponsor commitments.

This calendar fatigue affects the sport’s fans in a number of ways. The increased number of events, proximity between events, and overlap of events creates the risk that fans become overloaded and forced to prioritise what events to follow. In the case of television coverage, the length of the season, the traditional “long format” of the current races and the preferences of digitally-native sports fans, have led to a reduction in overall viewership, an increase in the age of the average viewer, and stagnation in the value of licensed professional racing content. Even in Flanders (Belgium), where cycling is amongst the most popular sports, viewership drops significantly as the season progresses. According to research by Belgian sports economist Daam Van Reeth, on Sporza (a public TV network), before the Tour de France, the average TV audience is close to 600,000; after the Tour de France this drops to 300,000. Before the Tour de France, 13 out of 18 World Tour races are broadcast (72%); after the Tour, only four out of eight are broadcast (50%). Race organisers have complained of the difficulties of selling broadcast rights and attracting roadside audiences. Team owners, managers and riders have complained that the length and breadth of the calendar raises the risk of injury and detracts from the development of their own fan engagement strategies. Journalists and broadcasters have said it is difficult to maintain interest in a sport so over-supplied with racing that does little to add to the season’s climax. It has been claimed in interviews for this research and elsewhere that organisers regularly give away rights or pay for their own broadcast, that media organisations refuse to negotiate for access because there is so little competition and that events live or die based on the charity of a single sponsor. In several criticisms of the earlier Pro Tour – the World Tour’s predecessor in name – top team managers such as Marc Madiot and Jonathan Vaughters cited the length and breadth of the calendar as being key reasons for withholding riders from certain events, skipping events, and the escalating costs of participating at the sport’s highest level. The problem was illustrated by the rise and fall of the Tour of Beijing, a race which was added to the calendar in 2011 and was cancelled after 2014. It was added as a legacy to build on the 2008 Beijing Olympics and to build cycling’s international popularity; however, the costs of adding cross-global travel costs, the late slot in the calendar (and the necessity for many teams to field tired star riders in the race), and the lack of sponsor interest led to strife between the UCI and the teams. These problems are even more pronounced beneath the World Tour level.

In short, the racing programme has become too long, crowded and unfocused. But there is huge potential for reform to move cycling towards a more contemporary calendar that makes the very fabric of the sport more exciting. Learning from its own history and the successes and failures of others, we could redraw the cycling calendar to better engage a new generation of fans. There are a number of principles that should inform those changes.

Future reform must, in its most basic form, be based on making the sport more entertaining and more engaging, responding to broader trends in audience preference and presentation. The calendar must therefore be shorter, prioritising consistency in the scheduling of events across the year to allow habits to form in a global audience and championing variety in styles of racing, moving beyond traditional point-to-point parcours to generate excitement amongst fans with a clear break from the past. It must allow a competitive narrative to emerge over the course of the season by creating opportunities for the best cyclists in the world to compete in the same races as often as possible. It must be possible for rivalries to emerge and play out weekly, rather than at random times of the year dependent on team and sponsor priorities. It must be easier to understand how the season unfolds, how races relate to one another and how fans should prioritise their viewing. A reformed calendar must elevate the impact of the most prestigious races, and it must discard the most irrelevant. It must be possible for a fan to discern the best cyclist at the end of each season, and for them to understand how the sport values in its riders’ performances.

The format of races themselves should also pursue simple principles for reform, as has already been trialled in some events with the addition of hill climb, criterium and circuit stages to traditional UCI level races. Grand Tours should seek to build on these developments to encourage more combative racing styles, with organisers experimenting with alternatives to the time-elapsed jersey model for judging performance and more varied stages. One day and one-week multi-stage races should follow suit, prioritising those strategies that make racing more exciting and bring fans closer to that excitement.

Further reform of the formats of professional cycling should find and engage potential communities of fans in under-exploited locations. In a bid to overcome much of the criticism levelled at multi-stage World Tour racing, professional cycling should develop and expand criterium racing to revitalise the sport and broaden the fan exposure, co-opting and expanding upon models trialled at the lower levels of the sport with considerable success. Shorter events fit the modern entertainment model. Criteriums and circuit races in downtown urban settings could provide spectators a live first-time or drop-in experience far more engaging than 200 kilometer point-to-point road races. In addition, city centre lap race venues, and also cyclocross courses, are tailor-made for television production teams, closely linking the broadcast and human resources to deliver content more cost-effectively, in parallel with local prime-time coverage. The predictability of lap times makes it possible to time the finishing sprint with the broadcast opportunities, increasing the probability of viewership, and hence creating greater opportunities for sponsors to engage with potential customers in a meaningful way. This type of racing should increasingly be structured around other types of entertainment, bicycle clinics, and product expos that can keep fans engaged throughout the entire race day.

There must also be a consistent effort to expand race locations beyond the traditional European strongholds of the sport, pursued with far greater emphasis on local preferences and cycling culture. All World Tour events should therefore be coupled with tourism opportunities and mass participation events to capitalise on opportunities for engagement, recognising that the combination of cycling as a sport and an activity could be a major driver for growth. Major event organisers have already experimented with tourism around key races in the World Tour calendar and these efforts should be pursued across the board in more diverse locations such as Asia and Latin America.

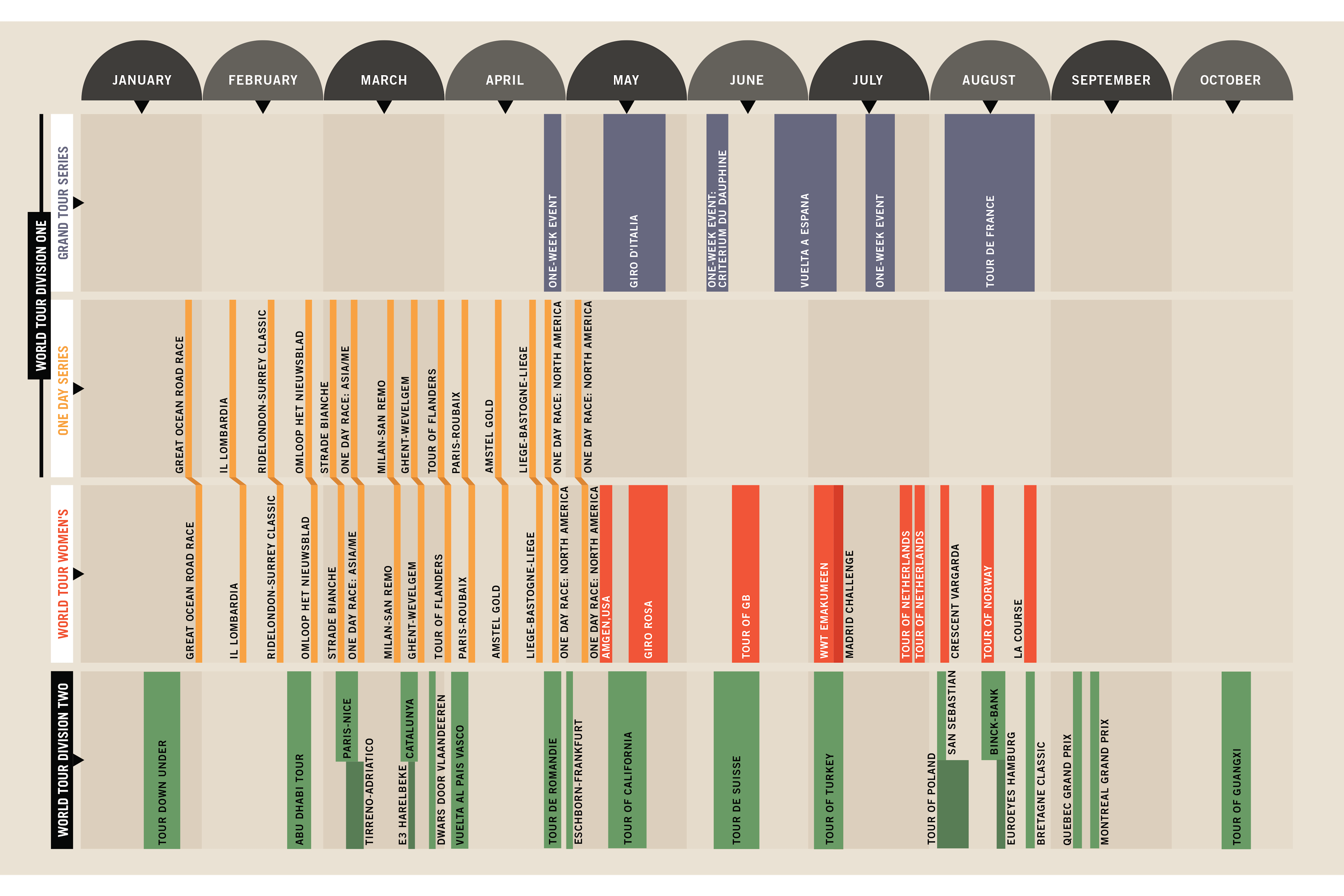

Based on the above principles and collating insights from each of the interviews conducted for this work, we propose the World Tour be split into two divisions, each with 15 teams, and World Tour events divided into two distinct racing series. Division One, comprising the 15 best cycling teams in the world, would replace the current World Tour status afforded to 18 teams in 2017. Division Two would be made up of the next best 15, taken from the current pool of World Tour and pro-continental squads. Promotion and relegation between the two divisions should be earned through performance in the racing calendar. Division One teams should be obliged to compete in two series in the cycling calendar; a One Day Series - renamed the Classics Series - and a Grand Tour Series. The Classics Series should include 14 one-day races, held every Sunday or on alternate Sundays between January and May around the world, depending on logistical and physical challenges presented by geographic spread of races and frequency. It should include all five Monuments (rescheduling Il Lombardia to fall between February and May) as well as seven other one-day races located in different regions around the world; Asia-Pacific, North and South America, Africa, the Middle East and Europe. It should mirror the F1 model; creating a recognisable infrastructure for one-day racing that is truly global and informed by local character on each stop of the tour, touring the world with a consistent presentation and timetable. There should be added consideration of the route and format of each race, favouring a timetable that encourages competition across the series. Riders wishing to compete in the Classics Series should be compelled by the event organiser to commit to racing all 12 events; it should not be possible to cherry pick one-day races without incurring a penalty, thereby ensuring racers regularly compete against one another and building a narrative into the season. Points should accrue based on performance in each race and a Classics World Champion should be crowned at the final race of the one-day season, in mid May annually. Every race in the Classics series should also include an equivalent women’s race as standard, junior events and a mass participation event in the same weekend. This should include a parcours with finishing circuit with ticketed entry. These weekends of racing and riding could be further expanded with junior and family-orientated events.

The Grand Tour Series, which would begin as the Classics Series finishes each year, would include the three existing Grand Tours as well as three optional one-week warm up tours scheduled before each of the main events. The Giro and the Vuelta should be shortened to two weeks each, and the Vuelta moved to before the Tour de France. Riders should not be required to race all three Grand Tours, but ensure they have accrued enough points to qualify for a place in the Tour de France, in which participation would be restricted to the highest performing riders of the year. A Grand Tour series would therefore conclude in August or September, with racing continuing at lower ranks, particularly in a second division of the World Tour, and providing space for other disciplines, particularly cyclocross and mountain biking to move to the fore during a clear off-season.

The current balancing of the Grand Tours - both in length and scheduling - denudes the Tour de France of its obvious position as cycling’s most important event. Whilst most sports ladder their season towards a climatic annual finale, professional cycling has organised a calendar which bookends its sporting pinnacle with less significant races. In so doing, it challenges fans to endure the remaining events of the season rather than reward them for their investment in the year to that point. The Vuelta and Giro should therefore be shortened, running before the Tour, and classified as a form of qualification for the season-ending Tour de France, which raises serious implications for the timetabling of these events that are likely to be resisted by event organisers. By the same logic, the road race of the UCI World Championships should be cancelled. The event holds little significance for fans or riders and primarily acts to confuse the presentation of the sport; participation is not linked to performance in the calendar in any way, riders race for their country of origin rather than their usual teams and there is a general failure to explain why fans ought to care about its existence. Within the Grand Tour Series, further reform should be sought to make the events themselves more engaging. Each stage of the race should be capped in length to no more than 160km and there should be a minimum number of hill climb, time trial and criterium stages. There have already been attempts to shorten and thereby excite racing in Grand Tours stages in recent years and interviewees regularly cited these as being largely successful. The image was often raised of a swelling peloton riding for hours on end through the French countryside as the greatest advertisement for the failure of professional cycling in the 21st century. A far more varied run of stages within Grand Tours, including city-centre circuits, very short stages and more creative use of the mountains coupled with the traditional use of longer stages to build suspence and intrigue, could be an antidote. Race points should accrue based on performance in the Giro and Vuelta, dictating qualification to the third and final Grand Tour; the Tour de France. All 15 teams in Division One of the Grand Tour should be invited to compete in the Tour de France, but they should be restricted in rider choice to those who accrued a certain number of points in the Classics Series and preceding two Grand Tours. There is a fundamental need to link events within the calendar, both to ensure riders regularly compete against their rivals and to reward fan engagement with an ongoing storyline in the calendar. Using a points model to determine participation in more prestigious events, and ultimately decide champions, is one way of doing that. It may also make the racing itself more exciting. It is worth noting that it may be necessary in such a system to introduce some form of ‘wild card’ provision allowing teams to select riders barred from accruing points through injury or illness.

The time-elapsed model for awarding victory in Grand Tour racing has also contributed to a culture of conservative riding, in which teams are orientated around conserving resources rather than using them. This has ultimately dulled the spectacle of professional cycling. There should be a debate therefore about how the winner of the Grand Tour Series, and the individual winners of the three Grand Tours, is decided. It may be necessary to structure a reward-model that is based on more than the simple “least time elapsed in the race” model that currently decided Grand Tour winners. Such a model could use much more dramatic time bonuses or point tables to make the race more competitive. The winners of the Classics Series and the Grand Tour Series should command the largest prize purse in the sport and race organisers could also be required to maintain heightened safety standards, timely payment of prize money, and to cultivate associated lower-level races in order to maintain their privileges and licenses as part of this calendar.

The remaining events of the existing World Tour calendar should become Division Two events, wherein the second division teams compete for promotion to the top league and access to the Classic and Grand Tour series.

With a narrowing of the World Tour calendar, more focus could be placed on events designed to build a narrative in the sport over the course of the year. Where the current calendar consists of largely unrelated and unconnected individual events, a revised structure could see races paced and weighted to emphasise the rivalries and performances within the sport. An alternate calendar could retain a strong connection to the sport’s rich history by maintaining cornerstones of the Grand Tours, the “Monuments” and other historically significant events but change where they fall within the year to avoid overlap as well as rider and fan fatigue and create the space for more radical innovation around the world.

Motorsports and redrawing the calender

Nearly every arena-based professional sport follows a calendar that builds from an off season, through a regular season, to playoffs followed by a championship. These calendars aren’t easily applicable to road cycling, but more suitable models can be found in the world of motorsports.

Formula 1’s season is a calendar of prime events in which individuals and teams collect points, which gradually build to well-defined and highly anticipated championship. A similar model is followed by NASCAR, but in addition to NASCAR’s prime draws, smaller events are held for drivers to test equipment, sharpen their skills, and build anticipation for headline races such as Daytona or Taladega. In recent years, NASCAR has experimented with an evolution of the tradition points-for-placings model, designed to create more compelling races and to develop stronger narratives (see next panel for more).

Below motorsport’s highest tiers, there is a host of minor championships, each defined by geographic reach and car class. These championships often feature as supporting races for higher calibre races, and serve to develop talent for the sport’s top teams - the structure of these championships, and their dual roles of talent development and under-card support, offers a model for the relationship between World Tour and ProContinental/Continental teams.

A new calendar could better geographically balance important legacy events in Europe with the possibility for existing or new races in emerging markets like Australia, China, Great Britain and North America. In its initial form, the calendar proposed above would offer considerably fewer racing days than the existing World Tour, but these would be more evenly spread geographically and across the season. (For a comparison of the existing and reformed racing calendars, see pages 30 to 33). The calendar’s improved sequencing and elimination of overlap could also reduce the logistical costs and travel impacts on the teams and athletes. Flexibility to adjust the calendar to meet changing fan demand going forward could also be preserved. Some top division races might be added or replaced by other established or newly emerging events, in countries like Colombia, Norway or South Africa, which have or are developing strong cycling cultures.

The racing calendar beneath the current World Tour is also in need of reform. The majority of interviewees for this work complained consistently that sub-World Tour racing was failing fans and riders around the world, despite being amongst the most accessible presentations of the sport and a vital talent pathway towards the elite ranks. There is reportedly a failure in both the organisation of events from a stakeholder point of view and the facilitating of events by national and regional governing bodies, both of which are regularly excused by severe lack of resources. As a result, there is a worrying decline in amateur road racing, particularly in Europe and the United States17, despite participation in cycling as an activity increasing. Between 2010 and 2015, the total number of races in Belgium, France, Italy and Spain fell from 194 to 161. This decline is especially visible in Spain where in 2015 only 20 races were scheduled down from 36 in 200018. This is explained in part by the broader economic model of the sport, discussed in more detail below. A side effect of the reliance on sponsorship as the near- sole source of revenue has been an over-investment in teams compared to races or events at the sub-World Tour level. The elite ranks have largely been able to survive this inequality, albeit with chronic instability, but the appeal of team sponsorship opportunities over race sponsorship opportunities has created a calendar beneath the World Tour that is almost incomprehensibly complex, unpredictable and which sees events appear and disappear with remarkable frequency.

Continue the conversation

#rapharoadmap