It’s an irrefutable fact that great stage racers make for dull stage racing. If you want a Giro worth watching, don’t trouble yourself with Merckx asphyxiation of the race 1972. Don’t subject yourself to the utter tedium which was Coppi’s 1953 “masterpiece”, because for three weeks it amounted to an infinite nothingness. So did Indurain’s 1992 Giro. The Italians never laid a glove on Miguelon, just as they’d never laid a glove on Anquetil in 1964.

Instead, immerse yourself in Pambianco’s 1961 odyssey, or in the high-wire act which saw Battaglin win in ’81. Then the pantomime villain Pollentier in ’77, Franco “Little Coppi” Chioccioli’s 1991 voyage of discovery, Savoldelli’s 2002 conjuring trick. What days they were, and what a madcap Giro that was.

The Giro invariably stands up when we least expected it, and 1962 was a case in point...

Would the Real Giro Please Stand Up?

In winning the 1962 Giro, Franco Balmamion prevailed in a civil war with a more famous, more celebrated team mate. Herbie Sykes uncovers the secrets of a truly great corsa rosa…

It would be the same, they informed us beforehand, but totally different. The same because it would be a three-week tour of Italy and the Italians, different because they – and their Bel Paese – were being rethought, reconfigured and reinvented. The economic boom was a matter of delirious fact now, and Italians had more free time and much more money. They had infinite ways of spending both, and so the “touristic Giro” had been engineered to help them. It would be harder, hillier and, at 4180 kilometres, longer than ever before. It would reacquaint them with the places they’d left behind in the rush towards urbanization, and would become the blueprint for subsequent editions.

Vito Taccone liked it a very great deal, and he was the darling of the south. He was a shitkicker from down in the Abruzzo, and there was nothing he loved more than thumbing his nose at those snooty northerners. He reckoned he could win this Giro, and so did each of Legnano’s joint leaders. The Ligure Graziano Battistini had been runner-up at the 1960 Tour, and lanky, tongue-tied Imerio Massignan was Italian cycling’s unwitting pin-up boy. Nobody had heard of him when he’d turned up at the 1959 race, principally because he’d been a professional cyclist for all of two weeks. His performance in the penultimate stage, over nine hours and 296 Alpine kilometres to Courmayeur, had changed all that though. The following year he’d almost won the thing outright, but then he’d punctured three times on the descent of the Gavia. The cycling gods had turned against poor Imerio and he’d lost the lot. He’d been inconsolable at the finish line, and his tears had melted the hearts of millions of Italians. Massignan, you see, was one of them.

The winner that day hadn’t been one of them at all. Charly Gaul was monosyllabic, foreign and just a little bit surly. The Italians had him down as antipatico, but nobody scootled up a mountain the way he did. He already had two pink jerseys, and everyone knew he had the ability to detonate the race in a single afternoon. If, heaven forbid, a straniero was to win this Giro, it would be him.

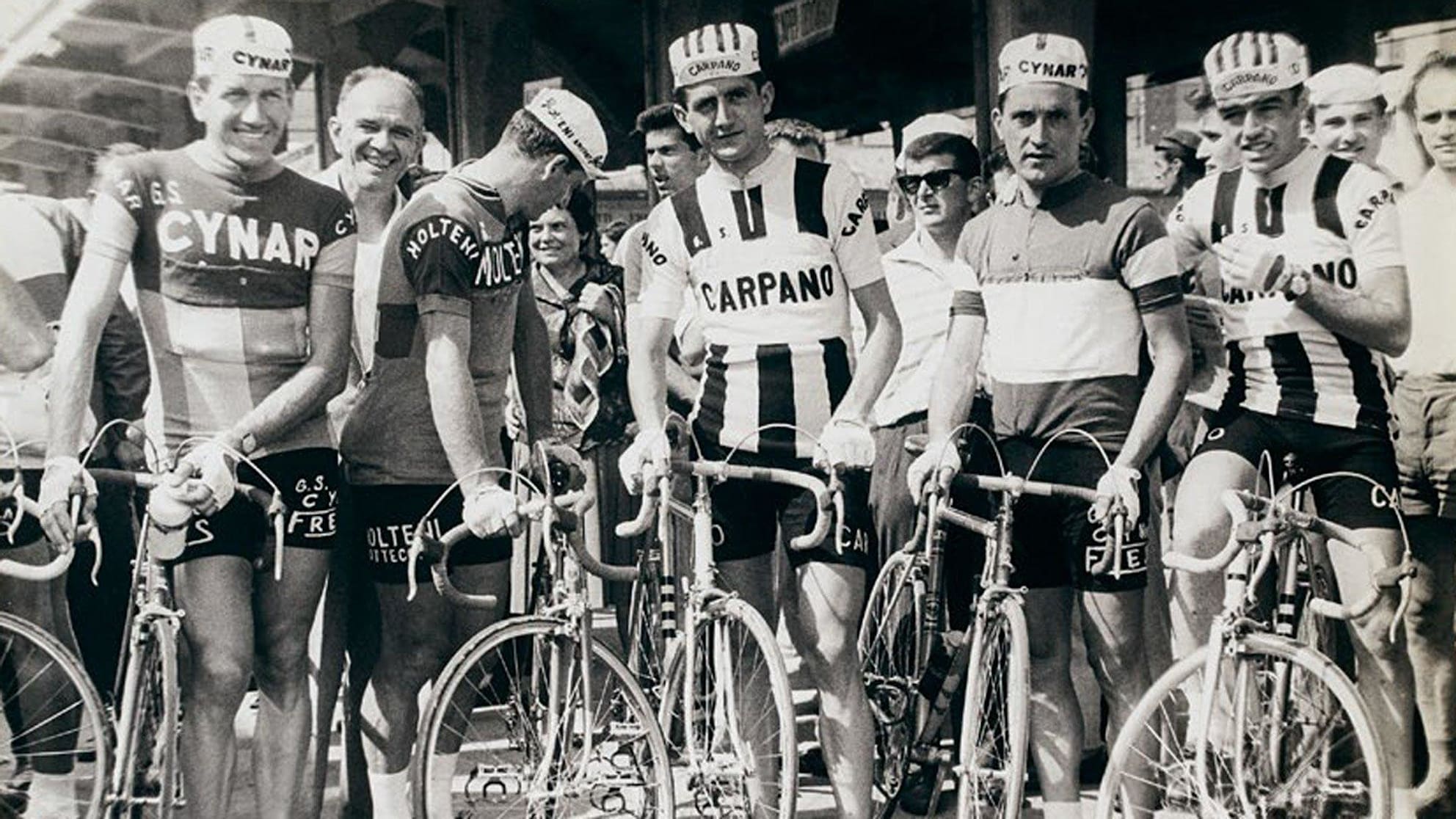

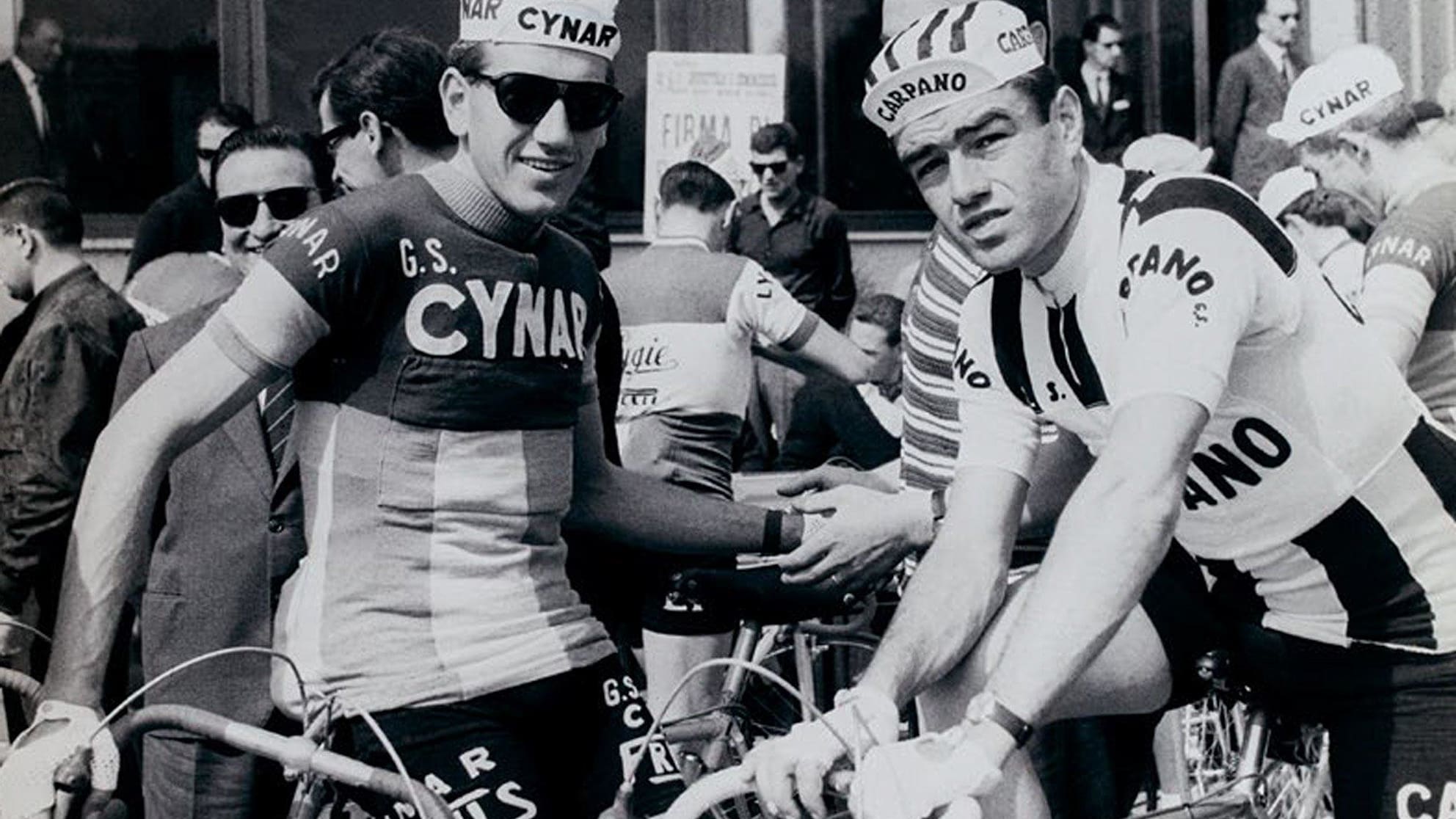

Gaul rode for Gazzola, a pasta maker from the loveliest Italian town you’ve likely never heard of. Mondovì’s an hour due south of Turin, and there the mighty Carpano had an elemental problem. They’d won the Tour, won the world team championship, won just about anything and everything which wasn’t the Giro. Of course that was the one they desperately, urgently wanted, and they’d thrown the kitchen sink at it. They’d had the best riders, the best bikes (made by the genius Pelà) and even, by common consent, the best jersey. The manager, Vincenzo Giacotto, was a big Juventus fan. He’d wanted to create a team with a Torinese identity, and so how better than to fill it with local riders kitted out like the calcio superstars Sìvori, Boniperti and Charles?

Carpano’s standard bearer was Nino Defilippis. He was Torinese to his bootstraps, and he was an authentic champion. He’d won seven stages at the Tour and seven at the Giro, and twice he’d been Italian national champion. He’d won Lombardy and a whole bunch of others, and he’d an ego to match his talent. Nino, however, had never much fancied the muck and nettles of the GC. He was a cracking climber, but he preferred stage wins, hearts and flowers to the daily grind of the maglia rosa group.

With that in mind, Giacotto had taken a punt on 22-year-old Franco Balmamion. Like Defilippis he was a fan of Torino, the “other” team in Turin, but that was about all they had in common. While Nino had Italy’s sports journalists in his very deep pockets, Franco was the strong, silent type. He was modest and studious, and he was riding this Giro having taken a year’s leave (unpaid) from the FIAT spares division. Nominally he was Giacotto’s GC guy, though his having asked to be kept on at FIAT suggested he wasn’t entirely convinced. Conventional wisdom had it that he was a year or two from the sharp end, though with a fair wind he might make it into the top six.

Anyway that, more or less, was the deal. Nino would help himself to a couple of stage wins, and Franco would try to hang with Taccone, Battistini, Massignan and Gaul. All clear?

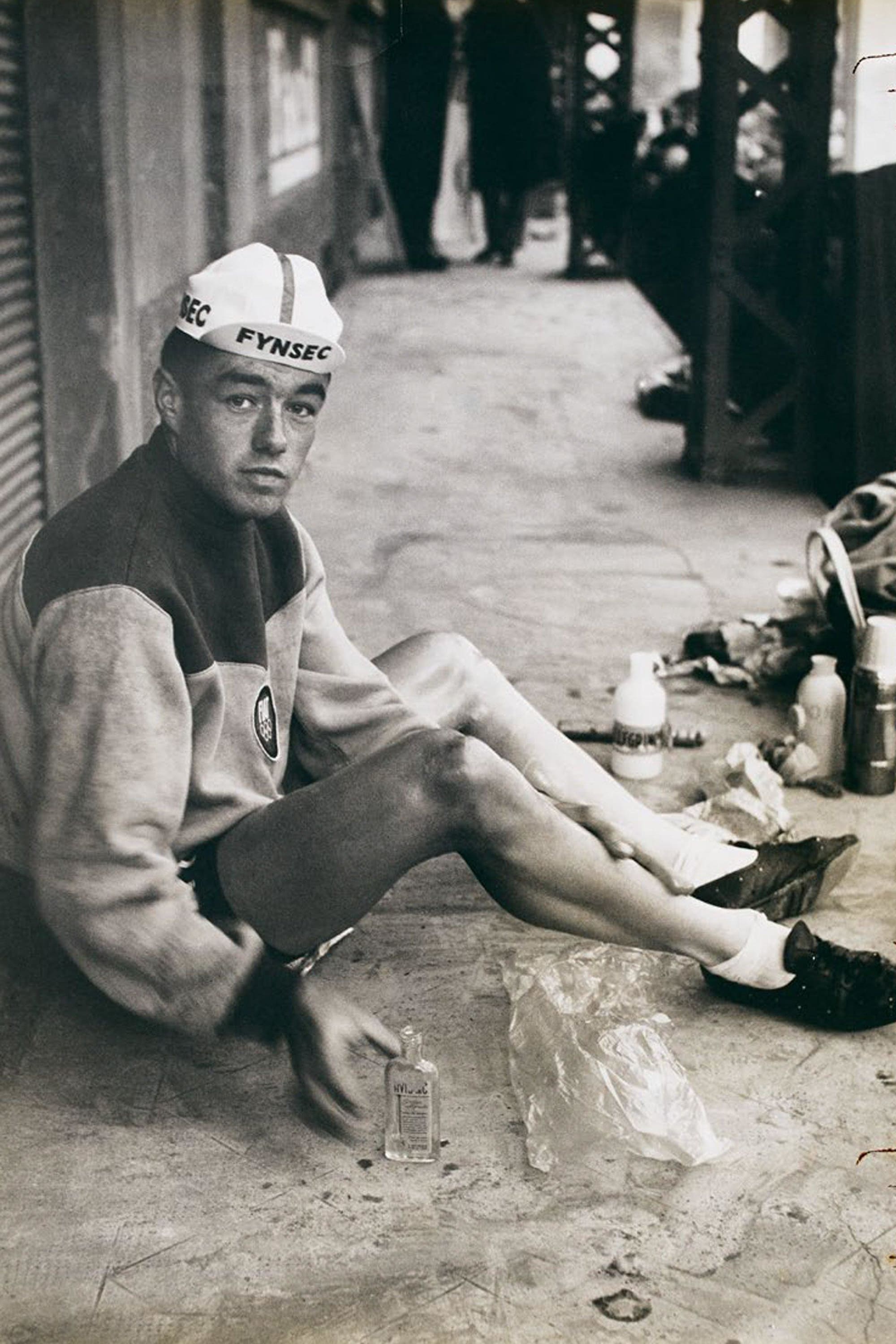

It rained sideways on stage two. Balmamion bonked and shipped eight minutes. Oh dear, or words to that effect.

Now Carpano had a big, ugly problem. They couldn’t not have a GC rider, so Giacotto invited Balmamion and Defilippis to contemplate a role reversal. Poor, chastened Balmamion would try to redeem himself by going with the breaks, and Defilippis would be seen to be altruistic in riding for GC. Nino, who didn’t know the meaning of altruism, had no choice but to accept, but he wasn’t happy. He wasn’t happy about the situation and he was very, very far from happy with Franco Balmamion.

On stage 14, a monster in the Dolomites, there was an authentic blizzard. Half the peloton abandoned, Gaul included, and that more or less ensured an Italian winner. Nino climbed off, but Balmamion towed him for 80 kilometres and got him back to the GC group. In so doing climbed to 11th and two days later he attacked and took three minutes. Thus, in advance of a transition stage towards the Alps, he stood seventh. Battistini led from the Spaniard Perez-Frances, while Massignan, Defilippis and Taccone were third, fourth and fifth respectively.

Balmamion was growing stronger with each passing day. The stronger he grew the more time he gained on the leaders, and the more time he gained the more it needled Defilippis. Nino had picked up the tab for the debacle on stage two, and whilst he’d been shackled to the GC group, Balmamion had ridden as he’d seen fit. He’d ridden, in fact, precisely as Nino would have had he not been compelled to mark time with the GC aspirants…

Nino, brilliant but famously capricious, was coming undone. He wasn’t accustomed to being tethered by team orders, and he certainly wasn’t accustomed to the notion that he was no longer the biggest fish in the Carpano pond. Objectively the team now had two chances to win the maglia rosa, and in theory that ought to have been a good thing. He hated it though, and Balmamion’s burgeoning strength and popularity made him feel insecure. He railed against the new meritocracy, not least because the Alps lay in wait and he knew that Balmamion was the better climber. In effect he was compelling Giacotto and the gregari to choose a side, in the hope that they’d choose his experience, his palmares and his celebrity over Balmamion’s youth and stage racing promise. The atmosphere was becoming poisonous, and the whole thing would come to a head one mad afternoon in their Piedmontese back yard.

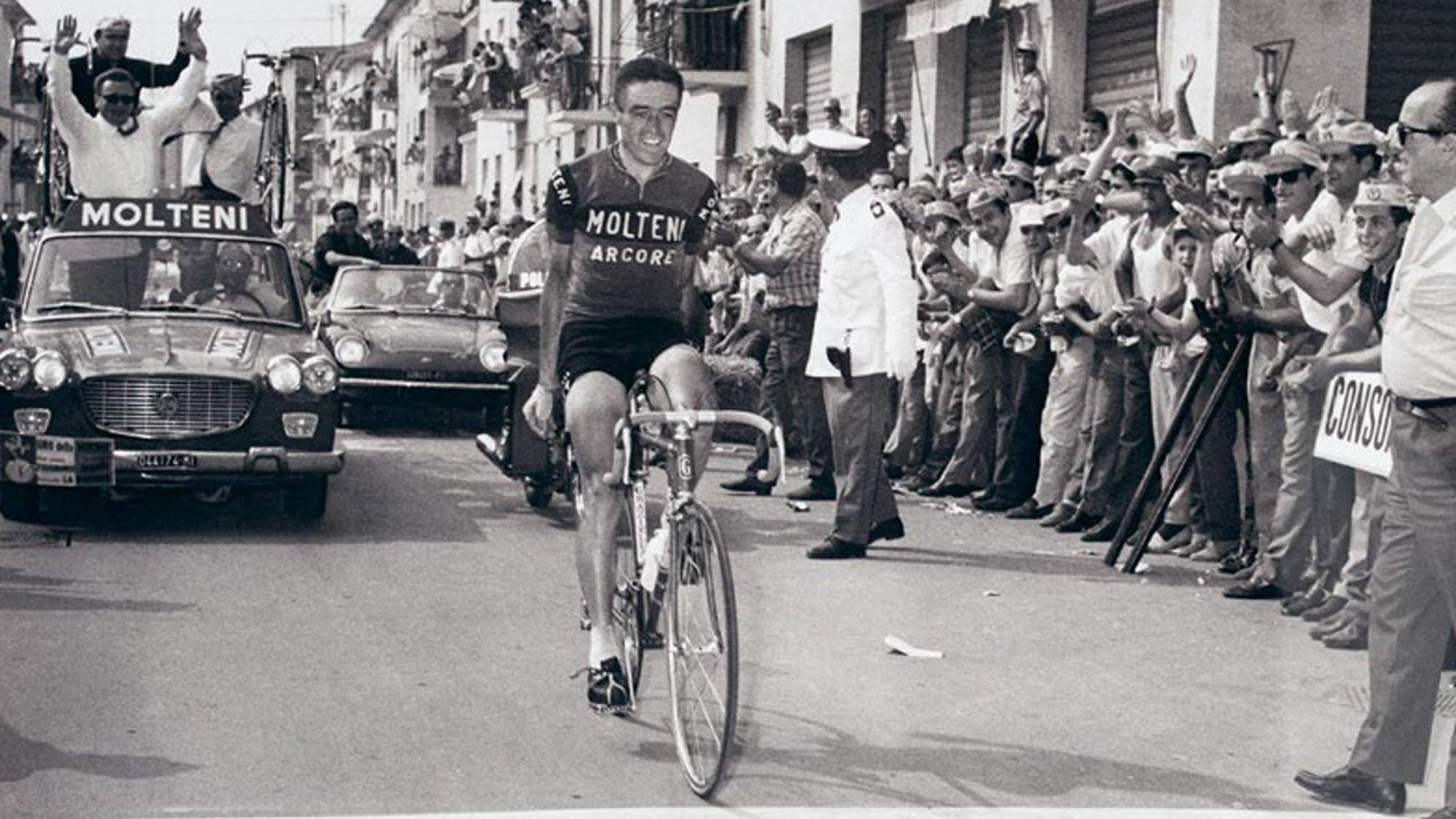

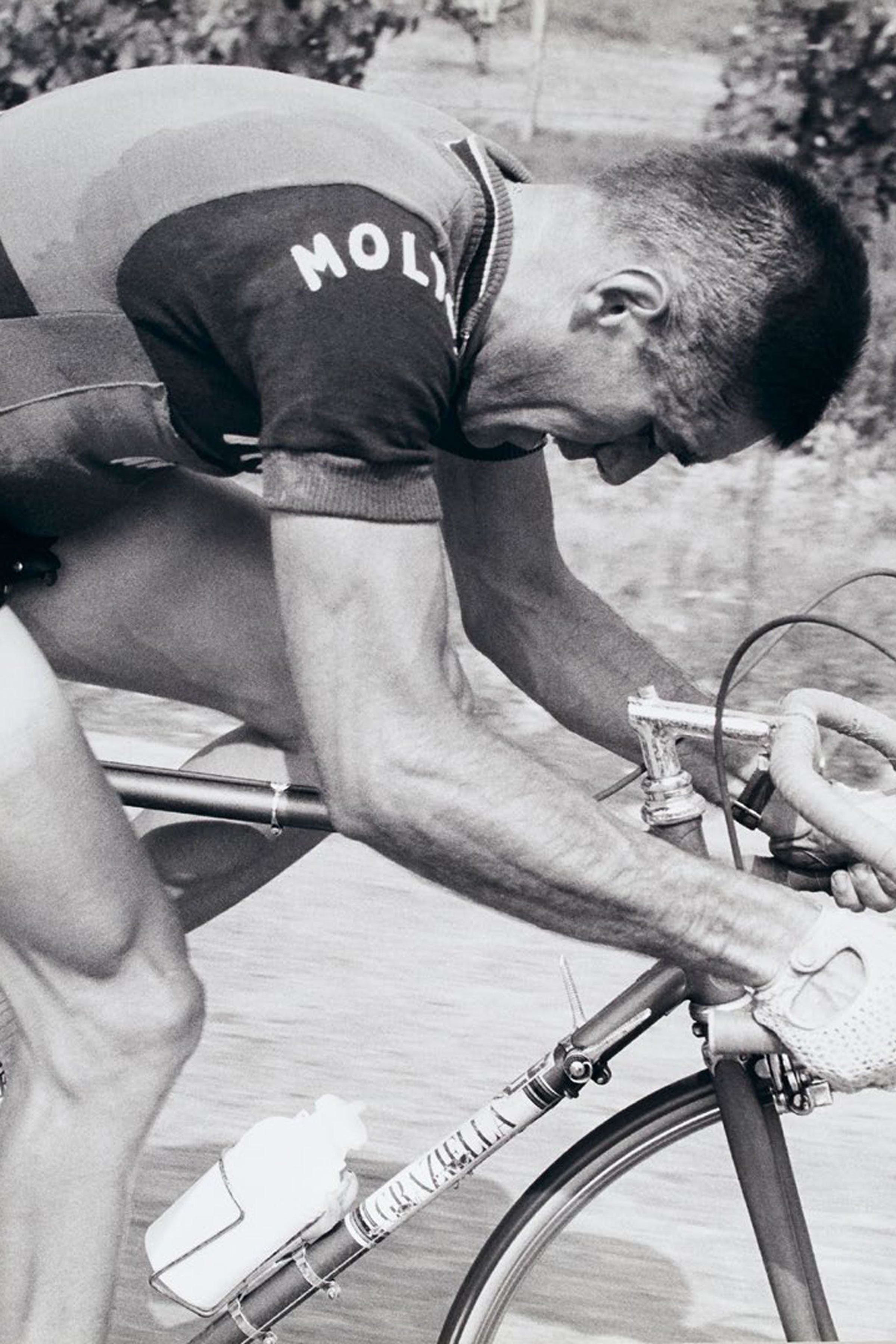

As stage 17 rolled off the shores of Lake Como, Nino launched an ferocious attack. He was joined by and handful of others, and that forced the maglia rosa Battistini, Massignan and their Legnano team mates onto the defensive. They went deep, and by the time they caught Nino they were powerless to do anything about the inevitable counter-attack. Balmamion quite rightly latched onto that, and he was joined by three strong Carpano passisti. Toni Bailetti was one of his best friends in cycling, and the Vuelta winner Angelo Conterno had been browbeaten by Defilippis for years. They threw Defilippis a bone by sending Giuseppe Sartore back, but they knew that if they got themselves organised they could propel Balmamion into Giro-winning contention. Molteni, who had the sprinter Armando Pellegrini in the break, knew that as well. Two of them agreed to work, and so now they were five...

As the gap grew, Nino climbed off in a fit of pique. He was persuaded, eventually, to remount, but with Legnano unable and Taccone’s Atala unwilling, Balmamion became virtual race leader. After four breakneck hours the break blasted into Casale Monferrato with a seven-minute advantage. While Nino seethed, the lesser-spotted Carpano climbed onto the podium and into the maglia rosa.

The four days which remained would be amongst the most compelling and (it must be said) most Italianate in the history of the race. The off-camera stuff beggars belief even for the Giro, but there’s always been more to Italian bike racing than Italians racing bikes. It’s intricate and far too Machiavellian to recount here, which of course explains why I felt compelled to write a book about it.

And so, dear reader, if you want to know how my favourite Giro was won (and lost) you’re just going to have to buy the damned thing…

Balmamion

Renowned cycling historian Herbie Sykes plots the history of the race’s least likely winner. Drawing on his immense knowledge of Italian cycling and personal encounters with a man he now calls a friend, Sykes introduces us to Franco Balmamion and retells the tale of his forgotten Giro win in 1962.

Buy now

Stay tuned for more Giro ‘62 stories as we bring you the race’s defining moments.